Omar Oakes: If you make $5bn a year from scam ads, are they a feature or a bug?

Scam ads don't persist on Meta because they are out of control. Eliminating them would mean slowing the very growth engines advertisers continue to fund.

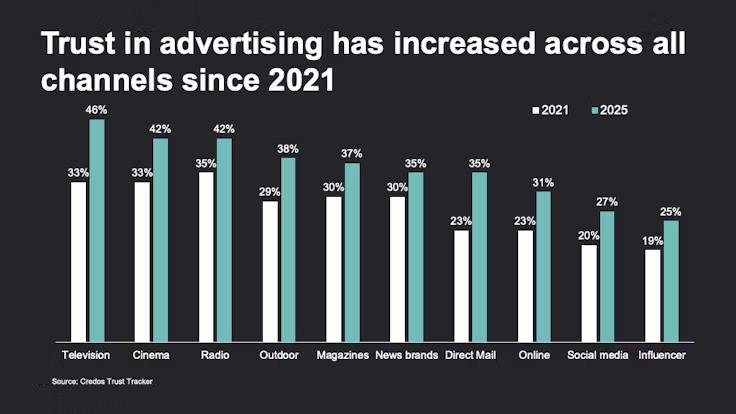

It should be a cause of embarrassment for an entire industry that fewer than half of people trust its core product.

And yet the UK’s three main advertising trade bodies — the IPA, ISBA and the Advertising Association — recently presented polling showing that only around 40% of the British public trust advertising, as if this were merely an unfortunate perception problem rather than a systemic failure.

A quarter of respondents said they actively distrust advertising. A further third described themselves as neither trusting nor distrusting — which, in truth, is likely to be a polite way of saying they are disengaged, sceptical, or resigned.

Bizarrely, this alarming Credos poll was presented as something to be “celebrated” about because trust has “reached its highest level in five years”.

The pollster’s director Dan Wilks fulminated said this was a “fantastic” result that “should be celebrated”.

Just imagine how deep the cynicism in advertising must run to truly embrace that point of view.

That a minority of people trusting your product is “fantastic”?

Industrial deception

Of course, I get that advertising as always traded in persuasion, so some exaggeration is expected. Some distrust is inevitable. Savvy consumers are assumed to understand the game.

But that logic collapses the moment deception stops being incidental and becomes industrial.

If you believe that scams and other forms of malicious deception have no place in a legitimate advertising ecosystem — that intentionally misleading people for profit is not just a creative excess but a fundamental breach — then you should be much more concerned with the underlying economics which incentivise these grifts.

Last November, Reuters reported that Meta internally estimated that as much as 10% of its global advertising revenue could be linked to scam ads and banned goods. That figure was striking not just because of its scale (one tenth!!), but because it suggested the company understood the problem so well that it could model it financially.

And at a LEAD conference, a senior Meta executive told the ad industry that the true figure was likely lower — a trifling 3-4% of annual ad revenue.

Except that, even on Meta’s own terms, that would still mean the company generated at least $5bn a year from ads that were fraudulent, deceptive, or indistinguishable from fraud.

“It’s higher than we would like it to be,” Amin said, adding that Meta expects it to fall as verification improves.

Is it though?

Again, imagine the cynicism it takes to believe “aw shucks, these platforms are victims. Criminals are so clever. And no system is foolproof.

It’s important to remind ourselves why that story no longer holds.

Because what Meta is describing here is not some kind of historic failure. It is a system working exactly as designed.

Abusers are still users

The key to understanding this is to stop treating scam advertising as an external rogue threat that occasionally breaches the castle walls.

It’s the outcome induced by the economic logic of Meta’s ad product.

Meta’s advertising machine is optimised around one overriding goal: frictionless growth at scale, particularly among small and medium-sized advertisers which make up around 80% of its ad revenue. (Frankly, it’s surprising Meta even bothers to send people to ad-industry events when it now makes relatively so little from large brands.)

So, for a local plumber or startup dating app, creating and buying an ad on Facebook or Instagram is fast, cheap, and accessible in a way no broadcast medium has ever allowed.

But frictionless onboarding has consequences.

When ads are easy to create, they are easy to abuse. When approval is rapid, deception moves faster than enforcement. When algorithms reward whatever converts most efficiently, scams — which are designed to exploit urgency, emotion, and asymmetric information — perform exceptionally well.

Enforcement, meanwhile, always lags volume. Human review cannot scale at the same speed as automated ad creation. Post-scam takedowns are structurally reactive. And verification, as Meta itself admits, is partial, phased, and unevenly applied across markets.

Put simply: the system selects for fraud.

Move fast and break things (that would increase costs)

This is why the language of “bad actors slipping through the net” is misleading. There is no meaningful “net” at the point of entry. There is a growth engine that relies on speed and scale, with enforcement layered on later in ways that minimise disruption to revenue.

Meta’s preferred defence is that this is simply the cost of operating at global scale. With billions of ads running each year, perfect pre-vetting is said to be technically impossible. Fraudsters adapt faster than rules. Any open platform will be targeted. Verification, therefore, must be gradual and risk-based.

At first glance, this sounds reasonable. It mirrors how we talk about crime in society at large. We accept some level of harm in exchange for openness and freedom.

But this analogy collapses under scrutiny.

Meta is not a country. Its platform is certainly not a free society, or digital town square, or anything like a system that resembles an actual human civilisation.

In reality, Facebook and Instagram are among the most heavily governed distribution systems ever built.

Its algorithms already exert extraordinary control over what content is seen, by whom, at what frequency, and with what amplification. The company routinely throttles reach, suppresses categories of content, demonetises accounts, and rewrites incentives overnight when it suits platform priorities — whether around political content, misinformation, or brand safety optics.

So the claim cannot be that Meta lacks the ability to exert control.

Meta chooses not to exert control at the point where it would introduce meaningful friction into advertiser onboarding and spend.

That distinction matters.

If fraud were merely an unavoidable externality, advertiser verification would be global, uniform, and non-negotiable. Instead, Meta’s own documentation shows that verification requirements are contingent on geography, advertiser type, and evolving policy thresholds. This creates arbitrage. Scammers can operate where rules are looser, shift jurisdictions, or mask identity with trivial effort.

Arbitrage only exists where enforcement is optional.

Which brings us to the uncomfortable implication for advertisers.

Advertisers are funding a scam-enabled system

Brands like to believe they are the customer in this system. In reality, they are just one class of revenue among many — and a relatively fragile one at that.

Individual advertisers, even large ones, are small and replaceable in the context of Meta’s total ad business. Fraud revenue, by contrast, is systemic. It does not negotiate. It does not threaten boycotts. It does not demand reputational assurances.

From a purely economic perspective, tolerating a low-friction environment that generates billions in fraudulent spend may be more important to the platform than appeasing a subset of brand advertisers with reputations to protect.

This is why advertisers are not neutral bystanders to this system.

Media budgets flowing into Meta are not just buying reach; they are subsidising an ecosystem that Meta itself concedes produces criminal revenue at scale.

And this is where the industry’s comfort with incrementalism becomes indefensible.

Verification is presented as the answer. But verification that can be phased, localised, deferred, and selectively enforced is not a safeguard. It is a growth management tool. It signals intent without materially disrupting the incentives that produce the problem in the first place.

Which leaves one conclusion that is hard to avoid.

Scam is not something in Meta’s advertising offer that can be minimised. Scam is baked into the whole offer as designed.

Not because ‘Meta wants crime’. But because crime thrives where speed, scale, and asymmetry are rewarded — and where the cost of eliminating it would be borne upstream, by growth.

And this is set to get worse

Once you see that, the question is no longer whether Meta is doing enough.

The question is why the advertising industry continues to fund a system whose harms are no longer accidental, and whose logic everyone can now see clearly.

Because last month we saw Meta’s ad revenue grow by 24% in a single quarter to just under $60bn.

Let’s pause a moment to reflect on this again.

Meta’s ad revenue grew by TWENTY-FOUR PER CENT to SIXTY BILLION DOLLARS in a quarter. That’s three months to earn the annual GDP of Myanmar (a country still scarred by Facebook’s enablement of a very much more horrific sort of organised crime). (Source: WARC Media (‘Media’s New Normal’ | Global Ad Trends, Dec 2025))

And there is no evidence that this rate of growth is stopping. As the recent WARC Media Global Ad Trends report I authored showed, Meta, alongside Alphabet and Amazon, are hoovering up nearly all of this industry’s growth.

What will then happen to trust in advertising when ever more of it only exists on a platform that continues to benefit so richly from scams?

This article first appeared in Ad-verse Reactions, a newsletter written by independent journalist and consultant Omar Oakes, covering the economics, power structures and unintended consequences shaping advertising and media. You can subscribe to Ad-verse Reactions for regular analysis at omaroakes.substack.com.

This article first appeared in Ad-verse Reactions, a newsletter written by independent journalist and consultant Omar Oakes, covering the economics, power structures and unintended consequences shaping advertising and media. You can subscribe to Ad-verse Reactions for regular analysis at omaroakes.substack.com.